|

|

Clin. Cardiol. 23, 883–889 (2000)

Anis Rassi, Jr., M.D., Anis Rassi, M.D., William C. Little, M.D.*

Section of Cardiology, Anis Rassi Hospital, Goiânia, Goiás, Brazil; *Cardiology Section, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA

Summary: Chagas' disease is caused by a protozoan parasite, Trypanosoma cruzi, that is transmitted to humans through the feces of infected bloodsucking insects in endemic areas of Latin America, or occasionally by nonvectorial mechanisms, such as blood transfusion. Cardiac involvement, which typically appears decades after the initial infection, may result in cardiac arrhythmias, ventricular aneurysm, congestive heart failure, thromboembolism, and sudden cardiac death. Between 16 and 18 million persons are infected in Latin America. The migration of infected Latin Americans to the United States or other countries where the disease is uncommon poses two problems: the misdiagnosis or undiagnosis of Chagas' heart disease in these immigrants and the possibility of transmission of Chagas' disease through blood transfusions. Diagnosis is based on positive serologic tests and the clinical features. The antiparasitic drug, benznidazole, is effective when given for the initial infection and may also be beneficial for the chronic phase. The use of amiodarone, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and pacemaker implantation may contribute to a better survival in selected patients with cardiac involvement of chronic Chagas' disease.

Key words: Chagas' heart disease, Chagas' disease, chronic chagasic cardiopathy, review

Chagas' disease results from infection with the protozoan, Trypanosoma cruzi. It was first described in 1909 by the Brazilian physician Carlos Chagas.1 He discovered the parasite, described the vector and the cycle of infection, and subsequently reported the signs and symptoms present in each phase of the disease. This parasitic infection is usually transmitted through the feces of an infected bloodsucking insect (the reduviid bug), although the infection can also occur by nonvectorial mechanisms, such as blood transfusion. The major manifestations are cardiac, including heart failure, arrhythmias, and thromboembolism. The disease is endemic in Latin America, most frequently in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, and Venezuela. It is estimated that 100 million individuals are at risk for infection and 16 to 18 million are infected.2

Although transmission of Chagas' disease by its insect vector is exceedingly rare in the United States, migration of infected individuals from Latin America poses two problems. First, a potentially treatable disease may escape recognition and diagnosis; second, there is a risk of transmission of the disease through blood or organ donation.

The life cycle of T. cruzi involves four distinct forms in insect vectors and mammalian hosts: (1) the epimastigote, present in the intestinal tract of the insect, that replicates; (2) the infective metacyclic trypomastigote in the vector's hindgut; (3) a blood stage form (trypomastigote) that penetrates mammalian cells; and (4) an intracellular form (amastigote) that replicates. Infection occurs when an infected bloodsucking bug bites and it defecates on the skin of a susceptible host. The metacyclic trypomastigotes in the feces produce a local infection when it is rubbed into the site of the bite (chagoma) or by penetrating the intact mucous membrane of the eye (Romaña's sign). Once inside the local reticuloendotelial and connective cells, the infective T. cruzi differentiates into amastigotes that begin replicating. When the cell is full of amastigotes, they transform once more and become trypomastigotes by growing flagellae. The trypomastigotes lyse the cells, infect adjacent tissue, and enter the bloodstream. Circulating trypomastigotes disseminate the infection by penetrating muscle cells (cardiac, smooth, and skeletal), neurons, lymph nodes, liver, and spleen. The cycle is completed when a reduviid bug becomes infected by ingesting the blood from an infected human or animal.

Most T. cruzi infections in humans are acquired from the insect vector, but may occur by transfusion of blood from an infected donor, even in nonendemic countries.3 Congenital transmission, accidental contamination, and transmission by organ transplantation are other possible routes of infection.

Trypanosoma cruzi produces disease during the initial infection (acute phase) and again decades later.4 Acute Chagas' disease usually affects children or young adults in endemic areas. It produces local inflammation at the parasite entry site, as well as malaise; fever; enlargement of the liver, spleen, and lymph nodes; and subcutaneous edema. Mortality in the acute phase occasionally occurs (<5% of cases) due to acute myocarditis and/or meningoencephalitis. In most infected persons, the illness is not diagnosed because of the nonspecific nature of the signs and symptoms and the lack of access of poor patients to medical care. In this phase, treatment with an antiparasitic drug, such as benznidazole, will usually cure the infection5 and prevent the chronic manifestations. If untreated, the manifestations of the acute disease resolve spontaneously within 4 to 8 weeks in approximately 90% of infected individuals. About half of these patients will never develop chronic lesions. They can be recognized by positive serological tests, but do not have electrocardiographic (ECG) and radiological evidences of involvement of the heart, esophagus, or colon. The other half of patients will develop megaesophagus, megacolon, and/or cardiac disease 10 to 30 years after the acute infection.6 A direct progression from the acute phase to a clinical form of Chagas' disease occurs in a few patients (5 to 10%).

Cardiac involvement is the most frequent and serious manifestation of chronic Chagas' disease and typically leads to arrhythmias, cardiac failure, thromboembolic phenomena, and sudden death.

The pathogenesis of the cardiac lesions appearing decades after the initial infection is incompletely understood. The failure of conventional histological methods to find parasites in the myocardium led to the hypothesis that autoimmune responses are involved in the late clinical manifestations.7 Studies in animals suggest involvement of cellular mechanisms, particularly CD4+ T lymphocytes, along with macrophage activation and inflammatory cytokine mediators.8, 9 It appears that self-reactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes develop following the initial infection and are able to lyse nonparasitized myocardial cells.10 Humoral immunity, expressed by a variety of antibodies against endothelium, vascular structures, and interstitium, have been implicated in the pathogenesis of Chagas' myocarditis,11 although not confirmed by other studies.12

Using very sensitive immunohistochemical techniques13 and the in situ polymerase chain reaction amplification methods,14 parasitic antigens have been found recently in the hearts of patients with chronic Chagas' disease. In addition, an association between the presence of T. cruzi antigens and the intensity of the inflammatory process was observed, suggesting a direct participation of the parasite in the genesis of chronic Chagas' myocarditis.15 It is possible that even low-grade persistent parasitisms serve as a continuous antigenic stimulus, and that both T. cruzi inflammation and an autoimmune response may play important roles in the pathogenesis of Chagas' heart disease.

Another hypothesis, based on the focal nature of the myocytolytic necrosis and experimental evidence of dynamic abnormalities of the coronary microvasculature associated with formation of platelet aggregates and thrombi, proposes that the microcirculation could participate in the disease process.16

Autonomic denervation is another typical finding and explains the digestive alterations (megaesophagus and megacolon).17 The specific cardiac parasympathetic impairment does not seem to produce myocyte damage,18 but could predispose patients to arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death.

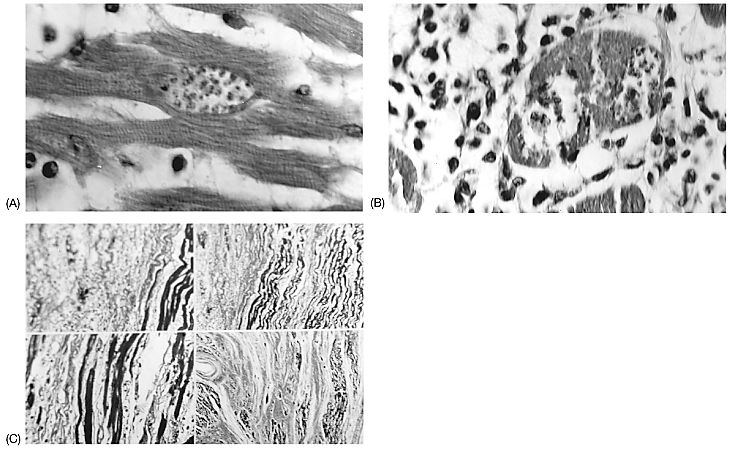

The chronic cardiac form of Chagas' disease is characterized by a focal inflammatory process composed of lymphomononuclear cells that produce progressive destruction of cardiac fibers and marked reactive and reparative fibrosis affecting multiple areas of the myocardium4, 19 (Fig. 1). The parasympathetic cardiac nerves and the conduction system are preferentially involved,20 producing intraventricular and atrioventricular (AV) blocks, sinus node dysfunction, and ventricular arrhythmias (Fig. 2). The right bundle and the left anterior fascicle are most frequently affected.

Fig. 1 Photomicrographs of ventricular myocardium in different stages of chronic Chagas' heart disease. (A) Intact muscle cell containing amastigote forms of T. cruzi forming a pseudocyst; no inflammatory response (hematoxylin and eosin stain). (B) Rupture of the pseudocyst with an intense lymphomononuclear inflammatory reaction (hematoxylin and eosin stain). (C) Marked interstitial fibrosis (in blue) replacing necrotic myocytes or separating muscle fibers (in maroon, Gomori trichrome stain). Courtesy of Prof. Edison Reis Lopes.

Fig. 2 Diagram of the pathophysiology of Chagas' heart disease. AV = atrioventricular,

IV = intraventricular, SSS = sick sinus syndrome.

The focal myocardial fibrosis provides the anatomic substrate for ventricular and/or atrial arrhythmias, predisposes to cardiac dilation and failure, and leads to formation of narrow-necked left ventricular apical aneurysms, a hallmark of Chagas' heart disease.21 Thrombi are often present in the left ventricular aneurysm and in the right atrial appendage. This may explain the common occurrence of thromboembolic phenomena in the systemic and pulmonary circulation.22

Chagas' heart disease is the most common cause of cardiomyopathy in South and Central America and, in endemic areas, it is the leading cause of cardiovascular death among patients between the ages of 30 and 50 years.

Chagas' heart disease is an arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Frequent, complex ventricular premature beats, including runs of ventricular tachycardia, are a common finding on Holter monitoring or stress testing.23, 24 They correlate with the severity of ventricular dysfunction, but can also occur in patients with preserved ventricular function. Episodes of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia are present in approximately 40% of patients with mild wall motion abnormalities and in 90% of those with heart failure, an incidence that is higher than that observed in other cardiomyopathies.24

Sustained ventricular tachycardia is another important finding.25, 26 It can be reproduced during programmed ventricular stimulation in approximately 85% of patients and seems to result from an intramyocardial or subepicardial macroreentry circuit usually located at the inferolatero wall of the left ventricle27 and not at the apex where the wall motion abnormalities are more predominant.28

Bradyarrhythmias are also prevalent in Chagas' heart disease and among them, sick sinus syndrome and second and third degree AV blocks are the most common. Not infrequently, ventricular tachyarrhythmia and AV conduction abnormalities coexist in the same patient.

Another typical feature of Chagas' heart disease is sudden death,29 which is caused by ventricular fibrillation in the vast majority of cases (Fig. 2). It can occur as the initial clinical manifestation of the disease. Bradyarrhythmia, thromboembolic phenomena, and, in exceptional cases, the rupture of the apical aneurysm, are other possible causes of sudden death.

Congestive heart failure usually evolves slowly, presenting in patients 20 years or more after the acute infection. Isolated left heart failure may be present in the early stages of cardiac decompensation, but by the time of presentation, biventricular failure is frequently present with peripheral edema, hepatomegaly, and limited cardiac output more prominent than pulmonary congestion.

Thromboembolic manifestations arising from mural thrombi in the cardiac chambers are relatively frequent.22 Although brain embolism is by far the most common clinically recognized feature (followed by limbs and lungs), at necropsy emboli are found more frequently in the lungs, kidneys, and spleen.

Gastrointestinal dysfunction (megaesophagus and/or megacolon) is the second most common manifestation of chronic Chagas' disease and is found in 5 to 20% of patients with cardiomyopathy. The megaesophagus produces dysphagia with odynophagia, as well as epigastric pain, regurgitation, ptyalism, and malnutrition in severe cases. Megacolon produces obstipation.

The diagnosis of Chagas' heart disease is based on the demonstration of antibodies directed against T. cruzi antigens by at least two different serological tests (indirect immunofluorescence, indirect hemagglutination, complement fixation, and immunoenzymatic and radioimmune assays), and a clinical syndrome compatible with the disease (Table I).

|

Table I Clinical suspicion of chronic Chagas' heart disease |

|

Typical features:

|

| Abbreviations: ECG = electrocardiogram, AV = atrioventricular, ETT = exercise treadmill testing, LAH = left anterior hemiblock, PVCs = premature ventricular contractions, RBBB = right bundle-branch block, SSS = sick sinus syndrome. |

The most frequent ECG abnormalities are ventricular premature beats, bundle-branch block, left anterior fascicular block, T-wave inversion, abnormal Q waves, variable AV block, low voltage of QRS, and manifestations of sick sinus syndrome. The combination of right bundle-branch block and left anterior fascicular block is very typical in Chagas' heart disease (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Typical clinical features of Chagas' disease in a 42-year-old man

from rural Brazil who presented with palpitations. (A) Electrocardiogram showing

right bundle-branch block, left anterior hemiblock, anterior Q waves, and frequent

premature ventricular contractions. (B) Two-dimensional echocardiogram showing

an apical left ventricular aneurysm.

Echocardiography is useful in the diagnosis of myocardial involvement.28 The most typical finding is an apical left ventricular aneurysm (Fig. 3) with or without thrombi, and/or posterior basal akinesia or hypokinesia with preserved septal contraction. In cases of advanced cardiomyopathy with cardiac failure, biventricular dilatation occurs without hypertrophy. Studies employing Doppler techniques indicate that abnormalities in left ventricular diastolic function may precede the development of systolic dysfunction.30

The presence of complex ventricular arrhythmias on Holter monitoring31 or the development of ventricular tachycardia during treadmill exercise32 identify patients with an increased risk of sudden cardiac death. Also, the relatively frequent presence of asymptomatic transitory arrhythmias and the association of ventricular tachyarrhythmia with sinus node dysfunction and/or AV conduction abnormalities in the same patient reinforce the usefulness of both tests.24

Patients with Chagas' heart disease frequently experience chest pain without evidence of coronary artery disease. Because Chagas' disease produces chest pain, left ventricular aneurysms, ECG abnormalities, and ventricular arrhythmias, it can mimic coronary artery disease. In nonendemic countries, the presence of normal coronary angiograms in such a patient should raise the suspicion of Chagas' disease.

Since Carlos Chagas' initial description, it is apparent that many patients remain asymptomatic throughout life; some have conduction defects and mild segmental wall motion abnormalities; some develop severe symptoms of heart failure, thromboembolic phenomena, and multiple disturbances of rhythm; and others die suddenly and unexpectedly in the absence of previous cardiac symptoms. In general, sudden cardiac death (usually due to ventricular fibrillation) is the principal cause of death, occurring in 55 to 65% of patients, followed by congestive heart failure in 25 to 30%, and cerebral or pulmonary embolism in 10 to 15%.29 Sudden death predominates in patients with less extensive myocardial involvement (without heart failure) and with significant ventricular arrhythmias, whereas pump failure is the principal mechanism of death in patients with congestive heart failure.

Antiparasitic therapy is indicated in the infectious acute phase of the disease and for the prophylaxis of reactivation of the infection in immunosuppressed patients.5 The recent findings suggesting that T. cruzi may play a role in maintenance of myocardial inflammation in the chronic phase of Chagas' disease,13–15 and the experimental observation of regression of hystopathologic lesions in mice chronically infected with T. cruzi treated with antiparasitic agents,33 suggest that antitrypanosomal drugs should also be administered to chronic patients. Furthermore, it has now been reported by some authors34–36 that chronically infected patients treated with antiparasitic agents and followed for up to 16 years were much less likely to develop cardiac abnormalities subsequently than do untreated patients.

The two effective antitrypanosomal agents for clinical use are benznidazole and nifurtimox, which was recently withdrawn from the market. Benznidazole is given in an adult dose of 5 mg/kg/day (5–10 mg/kg/day for children) administered every 12 h for 60 days. Both drugs may cause side effects including dermatitis, polyneuritis, leukopenia, and gastrointestinal intolerance, sometimes requiring discontinuation of treatment.

Management of the clinical manifestations of Chagas' heart disease is based on the treatment of similar cardiac abnormalities produced by other cardiomyopathies.

Severe bradyarrhythmias are treated with pacemaker implantation, but the electrode should be placed in the subtricuspid area, not in the right ventricular apex. Apical fibrosis is common in Chagas' disease and may result in failure of a pacemaker placed in the apex to capture. Ventricular pacing in patients with Chagas' heart disease and advanced conduction abnormalities appears to improve survival compared with historic controls in whom this treatment was not possible.29

Although there is no evidence from randomized controlled trials that antiarrhythmic drugs prolong life or prevent sudden cardiac death in Chagas' heart disease, we recommend the use of empiric amiodarone for patients with sustained and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, particularly in the presence of significant myocardial dysfunction. Amiodarone is a potent antiarrhythmic drug that markedly reduces the severity and complexity of ventricular arrhythmias in patients with Chagas' disease,37 does not have negative inotropic properties, is well tolerated (when administered at low doses), has fewer proarrhythmic effects than class I agents, and may reduce total mortality and sudden cardiac death in patients with heart failure of other etiologies.38

For example, Rassi et al. compared the survival of 34 patients with Chagas' disease and sustained ventricular tachycardia, treated with amiodarone, with an earlier matched cohort of 42 patients not treated or receiving class I agents. Survival rate at 1 year (87 vs. 57%), 4 years (65 vs. 22%), and 8 years (59 vs. 7%) was significantly greater in the treated group.29

In patients failing empiric amiodarone therapy, electrophysiologic guided antiarrhythmic therapy has been advocated by some authors.26 Implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator should be considered for patients with refractory and hemodynamically unstable sustained ventricular tachycardia or for survivors of sudden cardiac death.24 However, to reduce frequent shocks, antiarrhythmic drug therapy is required in most patients because of the high prevalence of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia.

Aneurysmectomy,39 surgical ablation,40 transcoronary chemical ablation,41 and catheter ablation42, 43 have been attempted in some patients, but efficacy and/or long term effects on survival and arrhythmia recurrence are not established.

Congestive heart failure responds to routine management, including sodium restriction, diuretics, digitalis, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. For patients with severe cardiac failure, higher doses of diuretics are usually necessary. Although no long-term controlled trial demonstrating benefits of ACE inhibitors in Chagas' heart disease has been reported, we recommend their use, even in asymptomatic patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, based on their efficacy in left ventricular systolic dysfunction of other etiologies.44 Although beta blockers45, 46 and spironolactone47 improve survival in heart failure due to other etiologies, they have not been studied in Chagas' disease. Beta blockers have been avoided in patients with Chagas' disease because of bradyarrhythmias and AV conduction defects, but spironolactone is a theoretically attractive therapy because of the major role that cardiac fibrosis plays in the disease.

For selected patients with end-stage heart failure, cardiac transplantation remains an alternative.48, 49 It has been performed in some patients with promising results. However, patients must be treated with antitrypanosomal agents, because of the possibility of T. cruzi infection reactivation with the concomitant use of immunosuppressive drugs.50

Dynamic cardiomyoplasty, another surgical option, was performed in a few patients with disappointing results.51 More recently, the Brazilian cardiac surgeon Randas Batista introduced a left ventriculectomy,52 applying it first to some patients with Chagas' disease with end-stage cardiomyopathy. However, other authors,53 in a small series of patients, found no satisfactory results in patients with Chagas' disease.

Because of the high incidence of thromboembolic phenomena in Chagas' heart disease, anticoagulants are recommended in patients with atrial fibrillation, previous embolic episodes, and apical aneurysm with thrombus, even in the absence of controlled clinical trials demonstrating their efficacy.

Chagas' disease is widespread in South and Central America. Although T. cruzi-infected insects are present in many parts of the southern and western United States, only a few cases of acute Chagas' disease resulting from vector transmission have been described in North America.54 This probably results from the better living conditions that discourage the establishment of domiciliary insect population, the lack of contact between people and infected vectors, and variations in the behavior of the North American species of the reduviid bug.

With migration from endemic areas, Chagas' disease is becoming a more frequent problem in the United States, where it is estimated that 500,000 to 675,000 Latin American immigrants may be chronically infected with T. cruzi.55 Because the manifestations of Chagas' heart disease are diverse and the disease is perceived to be extremely rare, it may be unrecognized in nonendemic countries.56 To diagnose and treat Chagas' heart disease correctly, clinicians in nonendemic areas must become more familiar with its characteristics.

Transmission of the disease is possible by contaminated blood transfusion or by organ transplantation from an infected donor and may become a serious problem.57 Since screening tests are not performed in blood banks of nonendemic countries, the best policy for the time being is not to accept organ transplantation and blood transfusion from Latin American individuals with a positive epidemiologic history.

Address for reprints:

Anis Rassi, Jr., M.D.

Anis Rassi Hospital

Section of Cardiology

Av. A, 453 - Setor Oeste

Goiânia (GO), Brazil 74.110-020

Received: September 30, 1999

Accepted with revision: November 11, 1999